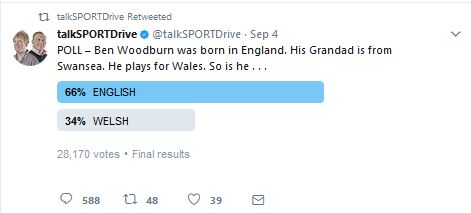

After footballer Ben Woodburn scored the winner in his debut for Wales, radio station TalkSPORT ran a poll asking people what nationality the 17-year-old really was.

The poll and its result are a reflection of how it is often assumed that people do not have the right to choose their nationality, and that it can be defined by certain requirements.

Controversies over national eligibility are not uncommon in sport. Football allows national qualification through the birthplace of any parent or grandparent.

Controversies over national eligibility are not uncommon in sport. Football allows national qualification through the birthplace of any parent or grandparent.

But there are no universal rules across all sports, and most do not even force athletes to commit until they have competed at senior international level. This has enabled a series of athletes and players to represent one nation at junior level and then another at senior level.

To tighten eligibility rules, and mute the effect of the economic pull of England on the UK population, the British football associations have agreed to not use FIFA rules that allow national qualification through two years of residency. This prevents the many overseas players in the Premier League qualifying for England but it also means that the British national teams do not reflect the cosmpolitan nature of a UK with 8.6m residents born elsewhere.

The Tebbit Test

The general flexibility of eligibility rules has led to accusations that athletes are choosing to represent a nation that they have no real affiliation with, simply because it offers an opportunity for career advancement.

After Wilfried Zaha, who moved to England as a child, chose to represent the Ivory Coast, despite having already won two English caps in friendly matches, England manager Gareth Southgate said it was not his job to sell the “passion of playing for England” to players. He added, “I’m English and proud to be English – part of your identity as a national team has to be pride in the shirt.”

Such words play into the hands of those who doubt the national commitment of ethnic minorities and people from overseas backgrounds. They are an echo of former Conservative MP Norman Tebbit’s 1990 claim that cricket was a test of loyalty that many British Asians failed by supporting India or Pakistan rather than England.

Surely reactions like this are products of how fragile some people’s sense of nationhood is. They see it as something to be protected from outsiders. Yet nationality by its very nature is something more complex than loyalty, the ownership of a passport or a place of birth. It is an unstable emotion, an idea and not a question of “either/or”. It can change with circumstance and time. It can mean very different things to different people.

Most importantly, those who seek to define nationhood without regard to its fluidity and complexity will undermine the very national cohesion they seek to protect. But nothing is more likely to alienate people from a community than questioning their loyalty to it.

Symbolic Inclusion And Exclusion

Until 1947, boxing operated a colour bar that required British champions to be British subjects, born of white parents and resident in Britain for at least two years. This created significant anger among British-born boxers from ethnic minorities. It was a clear statement that they were not regarded as British.

Following government and media pressure, the rule was replaced by eligibility through birth. This caused new tensions in the 1960s since it prevented men who had migrated as children from becoming champions of the nation they had grown up in. As a result, in 1968, a ten-year residency rule was introduced. And so, in 1970, Bunny Sterling became the first black immigrant to hold a British boxing title.

ALSO READ: Football’s Summer Transfer Window Showcases Changing Power Dynamics

Such symbolism matters. It is far easier for anyone to feel allegiance to a nation that recognises them as part of it. But this also means recognising the complex nature of nationhood and the continuing pull of old ties. Given how many individuals move in search of work or safety, the flexibility of sporting eligibility is an important reflection of the realities of a transnational world.

This is particularly true of the UK where the four nations have had centuries of demographic intermingling. At the 2011 census, a fifth of the Welsh population were born in England and 390,000 of them recorded their national identity as English. So, however Ben Woodburn regards himself outside football, he is still representative of a significant proportion of the Welsh population.

Other groups are not so lucky. Under British football rules, immigrants to the UK without a parent or grandparent born there, can only play for a British national team if they have five years of education in the country. Yet if they support any other nation they open themselves up to accusations of failing the “Tebbit test”.

The post-Brexit climate has already made many UK residents from other parts of the EU feel unwanted. Overcoming that means accepting their complex national identities.

Recognising their right to support or represent the team of their family roots would be a sign of respect. But picking a migrant for a British national team would also be a symbol of acceptance and a recognition of the realities of modern British society. It might even help on the pitch, too.