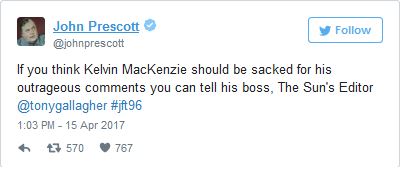

Kelvin MacKenzie has been suspended as a Sun columnist for an opinion piece in which he referred to Everton footballer Ross Barkley – who has a Nigerian grandfather – as a “gorilla”. MacKenzie also used the column to imply that the only wealthy people in Liverpool – other than footballers – are drug dealers.

Media commentators have since expressed incredulity on how the article passed journalistic checks and balances and found its way to publication. Focus shifted to the editorial process after MacKenzie stated that he was unaware of Barkley’s heritage. Sean O’Grady, of The Independent, noted: “The more disturbing question is how it came to be that all the various editors, subeditors and maybe lawyers through whose hands this in any case offensive article went appear not to have raised a query.” Peter Preston, a former Guardian editor, said in his Observer column that The Sun has “an executive hierarchy – from subs to night lawyers to supreme authorities – there to watch his back”.

Media commentators have since expressed incredulity on how the article passed journalistic checks and balances and found its way to publication. Focus shifted to the editorial process after MacKenzie stated that he was unaware of Barkley’s heritage. Sean O’Grady, of The Independent, noted: “The more disturbing question is how it came to be that all the various editors, subeditors and maybe lawyers through whose hands this in any case offensive article went appear not to have raised a query.” Peter Preston, a former Guardian editor, said in his Observer column that The Sun has “an executive hierarchy – from subs to night lawyers to supreme authorities – there to watch his back”.

However, to suggest anyone beyond the newspaper’s power-brokers are partially to blame for MacKenzie’s latest outrage is both misleading and disingenuous as it does not tally with the realities of newsroom culture. I write from the position of someone who worked in The Sun newsroom for nine years between 2000 and 2009 as a sports sub-editor and certainly didn’t consider myself to be part of an executive hierarchy.

However, to suggest anyone beyond the newspaper’s power-brokers are partially to blame for MacKenzie’s latest outrage is both misleading and disingenuous as it does not tally with the realities of newsroom culture. I write from the position of someone who worked in The Sun newsroom for nine years between 2000 and 2009 as a sports sub-editor and certainly didn’t consider myself to be part of an executive hierarchy.

‘SACRED MONSTERS’

Meryl Aldridge, of Nottingham University, uses the term “sacred monsters” to refer to leading industry figures such as MacKenzie in her 1998 article “The tentative hell-raisers: Identity and mythology in contemporary UK press journalism”. Aldridge noted how obsessed the newspaper industry was with larger-than-life characters and outrageous behaviour and considered these mythologies to be a crucial part of journalism’s collective identity. Aldridge made a significant point that the nostalgia around Fleet Street’s “golden age” is more rigorously asserted as journalism is increasingly subjected to intensified and routine work practices.

This myth-making around industry figures such as MacKenzie looms large in The Sun newsroom. Famous (or notorious, depending on your point of view) Sun front pages – many of which were published under MacKenzie’s editorship – adorned the corridors of the paper’s former Wapping home featuring headlines such as “Freddie Starr Ate My Hamster” and “Gotcha” (the latter marking the sinking of Argentina’s cruiser General Belgrano during the Falklands War). But it can also be used to intimidate. This romanticism and nostalgia hid a 1980s culture of bullying and loose ethical practices tolerated through newsroom ideologies such as “getting the story at all costs” and the “end justifying the means”.

This myth-making around industry figures such as MacKenzie looms large in The Sun newsroom. Famous (or notorious, depending on your point of view) Sun front pages – many of which were published under MacKenzie’s editorship – adorned the corridors of the paper’s former Wapping home featuring headlines such as “Freddie Starr Ate My Hamster” and “Gotcha” (the latter marking the sinking of Argentina’s cruiser General Belgrano during the Falklands War). But it can also be used to intimidate. This romanticism and nostalgia hid a 1980s culture of bullying and loose ethical practices tolerated through newsroom ideologies such as “getting the story at all costs” and the “end justifying the means”.

Which brings us to the present. Newspaper journalism’s obsession with sacred monsters, nostalgia and golden ages are hugely out of step with modern public thinking about those times. They also make for highly uncomfortable 21st-century newsroom environments. There is a clear and obvious disconnect between the industry’s lionisation of MacKenzie and the intense public revulsion felt towards him for “The Truth” headline, published shortly after the 1989 Hillsborough disaster.

SCAPEGOATS

This obsession explains two things. First, how MacKenzie continued to be employed by The Sun and, second, why this latest controversial article was seemingly published without basic checks being performed. Newsroom hierarchies across the industry tend to be reflected in the extent to which individual journalists are subjected to a rigorous sub-editing process. Checks and balances are not seen as helping out but are perceived as an affront to the most senior journalists. Blaming the subs is a familiar excuse that conceals these newsroom inequalities. This scapegoating simply serves power by hiding them.

Shop-floor journalists begrudgingly tolerate this preferential treatment, as well as the prospect of incurring disciplinary action if they displease the sacred monster, because of the professional logic of separating personal beliefs from journalistic practice (a similar rationale that enables Remainer journalists to work for pro-Brexit newspapers). At the same time, they glean a sense of occupational and institutional identity from these wider mythologies.

These nostalgic narratives are also more powerful than rational business decisions within the news media. MacKenzie’s reported £300,000 salary for his column is difficult to justify in an industry that is struggling financially, subject to regular swingeing newsroom cuts and is increasingly turning to casual, zero-hours labour. It is difficult to see how MacKenzie’s pay packet represents fair market value in terms of attracting readers and advertisers.

These nostalgic narratives are also more powerful than rational business decisions within the news media. MacKenzie’s reported £300,000 salary for his column is difficult to justify in an industry that is struggling financially, subject to regular swingeing newsroom cuts and is increasingly turning to casual, zero-hours labour. It is difficult to see how MacKenzie’s pay packet represents fair market value in terms of attracting readers and advertisers.

MacKenzie’s privileged position at The Sun is due to his longstanding association with Rupert Murdoch – and there’s the rub. Newspaper organisations have constructed a powerful mythology around individuals who are at the apex of inter-locking, networked hierarchical relationships at executive and proprietor level. These sacred monsters are generally above any standard journalistic checks and provide an intimidating presence to those who dare to do so. It is this power play that is responsible for MacKenzie’s article going to press. Not the subs. Not the section editors. Not the lawyers.