The Scottish national football team’s last gasp 1-0 victory over Slovenia in the World Cup qualifier on Sunday March 26 has breathed some life into a campaign that was trundling towards elimination. The Scots are now fourth of six nations – two points off second-placed Slovakia but six behind table-topping England, aka the Auld Enemy.

It will take more than one home win to lift the long-suffering Tartan Army, however. Next year it will be 20 years since Scotland’s legendary fanbase last saw their nation reach the finals of any international football tournament. That World Cup 1998 in France was a typically Scottish outing that lurched from heroics (against Brazil) to disaster (Morocco). In hindsight it was the end of a golden era stretching back to the late 1960s.

It will take more than one home win to lift the long-suffering Tartan Army, however. Next year it will be 20 years since Scotland’s legendary fanbase last saw their nation reach the finals of any international football tournament. That World Cup 1998 in France was a typically Scottish outing that lurched from heroics (against Brazil) to disaster (Morocco). In hindsight it was the end of a golden era stretching back to the late 1960s.

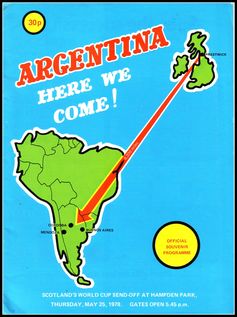

For a time, Scotland was to world-class footballers what Detroit was to soul singers. Big names, including Denis Law, Archie Gemmill, Jimmy Johnstone, Kenny Dalglish and Alan Hansen seemed to come off an endless production line of navy blue talent. The Scots barely missed a World Cup in that era and just about looked like contenders in 1974 and 1978 – albeit snatching romantic defeat in the opening rounds from the jaws of victory each time.

Having watched other small countries such as Iceland and Wales perform spectacularly well at Euro 2016, the question for a sports coach like me concerns how to get back to those glory days. I ask myself “what would I do?” in the shoes of Malky Mackay, the Scottish Football Association (SFA)‘s new performance director.

Having watched other small countries such as Iceland and Wales perform spectacularly well at Euro 2016, the question for a sports coach like me concerns how to get back to those glory days. I ask myself “what would I do?” in the shoes of Malky Mackay, the Scottish Football Association (SFA)‘s new performance director.

Under the microscope

The Scottish system certainly looks broken. It is questionable whether there are any world-class players any more and the domestic leagues are not providing a quality product for their fans.

The reasons are complex. Clubs protect their financial interests while only paying lip service to the national game. Meanwhile, professional players hold too much power, their managers are typically employed for who they are rather than their skills and the working-class communities that supplied the talent no longer exist in a coherent form.

I see an SFA board that’s expertise is mainly in big business. I see successful ex-players, such as Mackay, who have lived inside the football bubble since boyhood. They have plenty to offer, but they must be willing to bring in outsiders with expertise in long-term athlete development systems and high-level performance.

Where there are good initiatives, they tend to be undermined. For example, the SFA has invested in a great programme that works with young children in seven schools around the country. But many of them also play for the big club academies, which judge them on metrics that come down to winning and money, threatening them with the exit if they don’t produce.

There’s not going to be much joy when even nine-year-olds are under this kind of pressure. Those who have fun and develop a love of the game will invariably improve as they mature, so it’s a false economy.

I worry about the influence of the 10,000-hour rule for producing elite performers. Youth development policies are designed to clock up the hours, despite good evidence that early specialisation is negative and that talent in prepubescent children is near on impossible to spot.

Focusing youth development on the big clubs’ elite academies also disadvantages players from many previous working-class hotbeds of football. Their families may not have the access to a car to take them to training and may not have the wherewithal to support a performance lifestyle. This at least has been recognised, with targets to cut the number of club academies from 29 to a more appropriate number for a small country. If the savings are reinvested in traditional community clubs, that will be a good thing.

Small wonder

Yet to understand a system that could be successful in a small nation such as Scotland, I spoke with Dagur Dagbjartsson, the head of coaching education at the Icelandic FA. There I discovered an almost perfect model of player and coach development.

Yet to understand a system that could be successful in a small nation such as Scotland, I spoke with Dagur Dagbjartsson, the head of coaching education at the Icelandic FA. There I discovered an almost perfect model of player and coach development.

Iceland’s system is small, unadulterated by money and grounded in a community spirit. Young people are enabled to succeed through the government, FA, coaches and players all working together with a shared philosophy. Football clubs are community-focused. They allow anyone to join, regardless of ability. Young players are encouraged to train and form tight bonds with friends. There’s a big emphasis on differentiating between players based on ability rather than age, meaning players face challenges appropriate to their level. Demoralising scores of 20-0 are not the norm – unlike in Scottish youth football.

Coaches who work with children under the age of ten are given priority in education, since they are seen as responsible for the next generation. Government sports policy also requires children to do three sports sessions at school per week, one of which is swimming, avoiding too much early specialisation.

All football clubs have a close relationship with and are funded by the FA, and generate further income from annual joining fees. Coaches get paid and so treat coaching as a second job, which might explain the FA’s success in getting large numbers qualified and also the strong work ethic that I detected.

Contrast this with the well-meaning volunteers who do most coaching in smaller clubs in Scotland and England. Many give up after a few years. Even for professional coaches in the UK, salaries are so low that many of the best head to North America.

Icelandic coaches are also given the autonomy to coach in the way they think best. The system values them as professionals, with education front and centre. There is no anti-intellectual culture or resistance to learning from outsiders.

We have a dream …

The challenge for a nation such as Scotland is to stop trying to emulate richer footballing countries and learn from the likes of Iceland. This will involve the Scottish government, SFA and clubs at all levels pulling together in a similar way.

It means a transparent vision from the SFA with young people, communities, coaching and coach education at heart. It means clubs truly recognising that business models which focus on short-term gain won’t develop young players in the long term.

It means programmes for young people that help build confidence, social skills, relationships, trust and an ability to overcome adversity. Iceland has developed a system which works in its environment. If Scotland can do likewise, it may yet be able to show the Auld Enemy, with all of its own problems of football underachievement, how to produce the next generation of Dalglishes and Laws.