Aeons before COVID-19 turned football’s sidelines into a scene reminiscent of an emergency room, fans of the sport had already observed an array of face coverings and masks adopted for a multitude of practical and celebratory purposes. Whether it was to protect a facial injury, to promulgate a culture, or to revel in victory, the sport has seen its fair share of visors and vizards of all shapes and sizes throughout the years.

Football is probably not the first sport that comes to mind when you think about facial protection. Sports like fencing and ice hockey share a much more apparent and continuous threat to the face and head. Though the threat may not be as immediately obvious in football, head injuries do occur with some regularity. Professionals have often turned to protective medical masks, to continue playing as they heal.

It’s suspected that footballers have worn protective face masks of some description since the inception of the game. Early masks were likely made of a moulded leather, before then moving to thermoplastics and carbon fibre. Today, clear masks on the market are made from acrylic, and are made to fit a ‘standard’ face shape. However, when you see professionals wearing a mask, they’re most likely wearing a custom nylon 3D printed mask, made to fit their face like a glove.

How it started…

The first time I remember seeing a protective mask worn by a footballer was on Paul Gascoigne, when he was playing for England against Norway back in 1994. I recall thinking, “I really wouldn’t want to mark that guy.” The mask made him seem so sinister.

Like a lot of 90’s children I grew up watching Gazzetta Football Italia, a Serie A highlights show on Channel 4. I’d wake up every Saturday morning to catch the show, chiefly to see one of my favourite players, former Roma, Sampdoria and Lazio defender Siniša Mihajlović.

Sinisa Mihajlovic of Lazio, wearing a specially designed facemask to protect his cheek

The dead ball specialist had a knack for getting himself clattered in the face and wore facial protection on numerous occasions during his 14-year spell in Italy. A no nonsense type who didn’t mind a bit of argy-bargy, the mask merely accentuated his toughness, generating an aura of sheer terror around him. The Hannibal Lecter look-alike seemed to have, as captain Quint from Jaws would put it, lifeless eyes, black eyes, like a doll’s eyes.

Who could forget Chelsea’s injury plagued 2016/2017 season, when they could have fielded a full eleven of masked players? Facial injuries to key players like Petr Čech, John Terry, Cesc Fàbregas and Diego Costa, led Dutch manager Guus Hiddink to comment, “We are a team with a lot of masks… we are a Zorro team!”

It would of course be rather remiss of me not to mention Dutch midfielder Edgar Davids in a retrospective about facial protection. The ex-Ajax, AC Milan and Juventus star began wearing protective glasses following a 1999 operation on his right eye for glaucoma. The wrap around goggles he wore, along with his bullish style of play and long distinctive dreadlocks, made Davids a truly iconic and standout presence on the pitch.

Indeed, face coverings can allow athletes to participate when they may not otherwise have been able to do so. However, much like a trip to your local supermarket these days, face coverings can sometimes be a requirement for participants in a sport. One such sport is blind football – one of the fastest growing sports in the world.

As the name suggests, blind football is an adaptation of football for athletes with a visual impairment. Played on a pitch that is enclosed by hoardings (to prevent the ball from going out of play), blind football teams are five-a-side – four outfielders and a goalkeeper. Goalkeepers, who must remain inside a small goalmouth area, are either partially or fully sighted. All outfield players are required to wear a blindfold, to ensure a fair playing field.

So, how do they know where the ball is?

Players locate the ball by listening out for a uniquely designed, low-bounce ball fitted with an internal bell. They receive constant guidance from teammates and coaching staff, the latter of which are strategically positioned around the pitch. The pitch plays an important role, where the purpose of the surrounding hoardings is also to act as an acoustic board which allows the players to determine their own location and that of other players. Though players are required to shout ‘voy’ before attempting a tackle, I’d still wear those shin-guards, just to be safe!

Spain is considered to be the home of the sport, where it has been played since the early 1920’s. Brazil are the current IBSA Blind Football World Champions, winning the title in Tokyo in 2014. The Brazilians’ defence of their title at the Tokyo Paralympic Games was greatly anticipated, before COVID scrapped those plans, which have since been rescheduled to August 2021.

Whatever the brand of football, there has been a long tradition of players celebrating using masks.

I have fond memories of the first time I saw a player use a prop in celebration, during a match between Fulham and Charlton in 2002. Fulham’s new Argentine signing, Facundo Sava, scored the only goal of the game, then produced a ‘Zorro’ mask from his sock, much to the adulation of the Fulham faithful. The fictional vigilante was a cherished character from Sava’s formative years, and although he only scored six times for Fulham, the prospect of seeing his trademark celebration created a huge sense of anticipation. Neutral fans everywhere willed him to score whenever he graced the field.

Even our heroes have heroes.

UK-based market research company OnePoll conducted a survey earlier this year which found that Marvel’s Spiderman is America’s second most popular superhero, just behind DC Comics’ Man of Steel, Superman. Peter Parker’s alter-ego is seemingly as popular among professional footballers as it is among fans of the comic book universe.

Ecuadorian Otilino Tenorio was one of the first players to adopt the friendly neighbourhood spider guise. The internationally capped forward always celebrated by producing a mask from his shorts, usually followed by a loose-hipped, salsa-style dance. He continued this tradition until his tragic and untimely death in a car accident in 2005. As an homage to his former international teammate, striker Iván Kaviedes produced a yellow Spiderman mask from his sock after scoring against Costa Rica in 2006.

This ain’t the end

The Premier League too has seen its share of Spidermen over the years. Though Arsenal fans are yet to see Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang’s Spiderman mask, the forward donned a Black Panther inspired mask against Rennes back in March 2019. The Gabonese star has a long history of masked celebrations and wore a Spiderman mask with some regularity during his spells at Saint-Étienne and Borussia Dortmund.

Ex-Newcastle midfielder and toon fan favourite Jonás Gutiérrez first adopted the Spiderman mask while playing for Real Mallorca in 2008. He made the move to St James’ Park that Summer, but fans had to wait over a year to see his web-slinging antics – quite a long time to carry a sweaty mask around in your shorts with no pay-off.

“I was in the cinema one day and I met a family. I was talking with the dad and his kids and I promised them the next time I scored I would put on a Spiderman mask”, Gutiérrez stated in 2008. “I did it for the kids. Maybe I will do it again – everyone says do it again. But the rules have changed and if I do it, I will get booked. It is a shame, but what can I do?

The rule change Señor Gutiérrez alluded to occurred in 2007 and was received with much disdain by football fans the world over. The amendment, according to law makers the International Football Association Board (IFAB), was “motivated by the potentially increasingly common practice of players wearing masks during matches, which could tarnish the image of the game.”

Law 12 (Fouls and Misconduct) of the IFAB rule book states: “Players can celebrate when a goal is scored, but the celebration must not be excessive; choreographed celebrations are not encouraged and must not cause excessive time-wasting. A player must be cautioned, even if the goal is disallowed, for: covering the head or face with a mask or other similar item or removing the shirt or covering the head with the shirt.”

Now, if you’ve ever scored a goal in a competitive match, you know that all bets are off when it comes to celebrations. So, it’s no wonder that there was a rather prolonged period of players receiving cautions in the aftermath of the rule change. To this day, players caught up in the emotion of the moment forget the repercussions, and many would say, as well they should. To inhibit one’s natural reaction in such away is to dilute one of the most passion filled moment for players and fans alike.

One may certainly argue that football has lost a lot of its character as a result of these evolving rules.

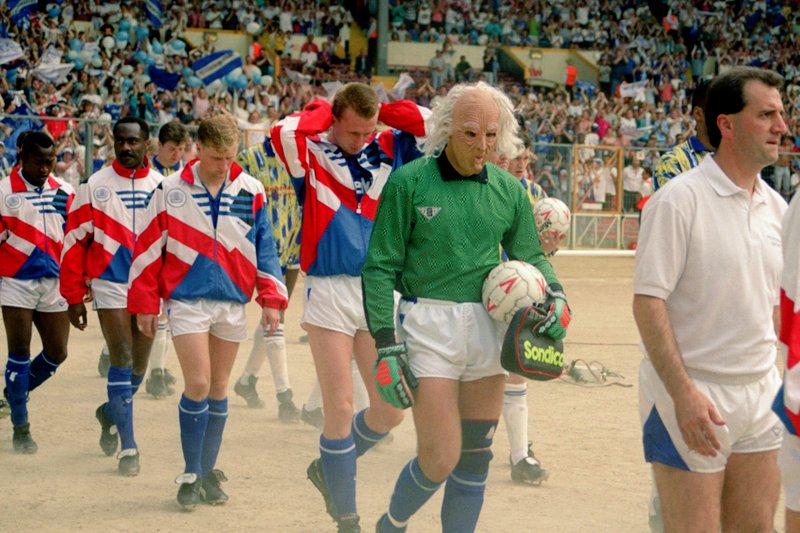

Some of you may recall eccentric former Peterborough goalkeeper Fred Barber, who’s calling card saw him don a Freddie Kruger mask from the film Nightmare on Elm Street.

When Posh made it to the play-off final in Wembley in 1992 the ‘keeper was told “it was not the done thing” at the home of football, but he wore the mask anyway. Before home games he would drop to his knees in front of the home-end and pray, all while wearing the horror mask. He was a whacky character, a cult favourite, but unfortunately, we won’t see his like again. There’s seemingly no room in the modern game for that level of expression.

Face coverings can also be a vehicle through which one expresses pride in culture. Wolves and Mexico forward Raúl Jiménez celebrated using a Lucha Libre (Mexican wrestling) mask on several occasions while playing for former club Benfica. Mexican wrestlers, known as luchadores, are hugely popular icons in Jiménez’s homeland, and as such the celebration holds a great personal meaning for him.

In 2019, after scoring a goal in the FA Cup semi-final against Watford, Jiménez pulled on a Wolves themed luchador mask, much to the delight of Wolves and wrestling fans alike. The mask in question was gifted to him by WWE wrestling star, and close friend, Sin Cara. The celebration, which drew some minor criticism from a somewhat confused public, coincided with ‘Wrestlemania’ and was intended as a nod to his warrior countryman.

Indeed, history’s ancient warriors have adopted facial protection as a piece of vital military equipment. Often decorated to instil fear in the opponent, masks have also been a source of great individual power. Samurai wore their richly decorated menpō and sōmen. The Maori struck fear in the hearts of their opponents by carving battle masks with designs that mirrored their tribal tattoos. Ancient Rome’s most heavily armed gladiators, the Thracians from northern Greece, adorned their helmets with the mythical Gorgon head – hoping it’s gaze would turn their enemies to stone.

Though no Thracian, Samnite or Gaul, Juventus and Argentina forward Paulo Dybala forms his own gladiatorial mask, one born out of a tremendous personal disappointment. His missed penalty against AC Milan in the 2016 Italian Super Cup, which cost his side the silverware, inspired the now famous celebration from which he draws so much fortitude.

In a 2017 interview the forward commented, “I went on holiday and was watching Gladiator on TV and that’s when I decided, for my next goal, to celebrate as a gladiator.‘Dybalamask’ is really simple: it’s the mask of a gladiator. When we struggle, sometimes we must wear our warrior mask to be stronger.”

I’ll leave you with one of the more thought-provoking news stories I’ve encountered since the beginning of the pandemic. Back in March most other nations had postponed all domestic fixtures, but Brazilian clubs were continuing to play-on, despite constant pleas from concerned players to scrap matches.

In protest, Grêmio players lined-up for their clash against São Luiz wearing face masks, fed up with being forced to play while infection rates in the country were sky rocketing. After the match, Grêmio boss Renato Portaluppi commented, “The whole world has stopped, shouldn’t Brazilian football stop as well? That’s our message and I hope they listen. We hope that good sense will prevail.”

So while we may long for the day when football can finally return to some semblance of normalcy, at least we can look back at a time when face coverings simply served to elevate our enjoyment of the game, and gave us a bit of a chuckle.