If a week is a long time in politics, then a month in football can seem like an eternity. The English Premier League January transfer window is now a well established tradition that can tease, delight and disappoint supporters in equal measure, delivering a ceaseless flow of news and half news all wrapped up in eye-watering spending by the clubs.

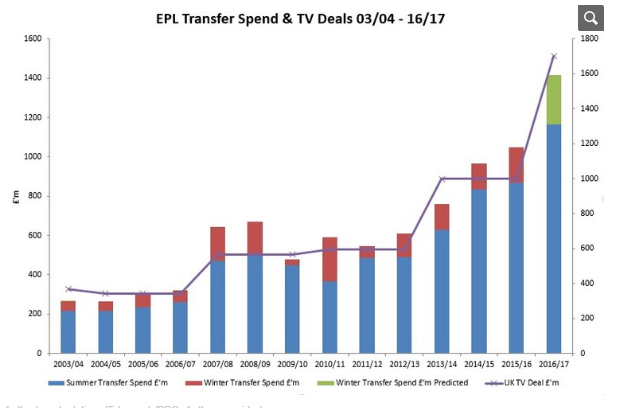

It is likely that this winter’s window will be the biggest yet, and is predicted to break the current record of £225m spent by clubs in 2011. The overall spending for the season should head past £1.4 billion – the summer 2015 window alone generated gross spending of £1.165 billion.

There are two factors at play in this prediction. First, the financial significance of staying in the League is bigger than ever. Holding onto a Premier League place is worth an estimated £130m to clubs so teams fighting relegation will feel under even more pressure to spend big. The risk here is clearly that their financial future could be threatened. Clubs can stretch too far, however, in tying players to big wages and long term contracts, an approach Queens Park Rangers followed with players such as Joey Barton, Bobby Zamora, Richard Dunne, Rio Ferdinand, Shaun Wright-Phillips, and Adel Taarabt. The club is now lying in 17th spot in the Championship, the second tier of English football.

Similarly, those clubs battling for a top six European spot, and for the European title itself, will be equally determined to ensure that their closest rivals do not buy the best talent.

Similarly, those clubs battling for a top six European spot, and for the European title itself, will be equally determined to ensure that their closest rivals do not buy the best talent.

Clubs also have more cash to spend than ever before. The signing of a £5.14 billion domestic broadcasting rights package means that clubs have the cash to strengthen their squad substantially. Coupled with overseas rights worth an estimated £3 billion, less the solidarity payments made to clubs in the Football League, Premier League clubs will have a total of around £7 billion to spend between them over the next three seasons – more for those who finish higher in the table. That’s before we factor in record club earnings, worth another £90m-100m based on estimates by football analysts at Deloitte.

It is therefore of little wonder that major competition for experienced players will drive up transfer values and annual salaries. So, what can we expect from this window?

Last season, January spending hit a five-year high of £175m, an increase of 36% on the previous year. With the 2016 winter window the first year of the new record TV deal, we can expect this figure to rise. There has been a steady increase in the amount of money spent on winter and summer transfers in recent times, increasing, for the most part, in line with each of the four broadcasting cycles, dating back to 2003.

This season’s summer spending has already eclipsed the combined summer and winter spend of last season. Of course summer spending far outstrips the winter window, a trend largely to be expected given that this is when clubs tend to change managers and build new squads in the off-season.

Winter spending is normally based on an objective, intensified by pressure from chairs, owners, fans, other clubs, agents and players themselves. Teams might need to improve short-term performance to stave off relegation, qualify for European competition or win the title. The financial loss from an error is so large that clubs feel the need to spend money to properly compete with their rivals.

Winter spending is normally based on an objective, intensified by pressure from chairs, owners, fans, other clubs, agents and players themselves. Teams might need to improve short-term performance to stave off relegation, qualify for European competition or win the title. The financial loss from an error is so large that clubs feel the need to spend money to properly compete with their rivals.

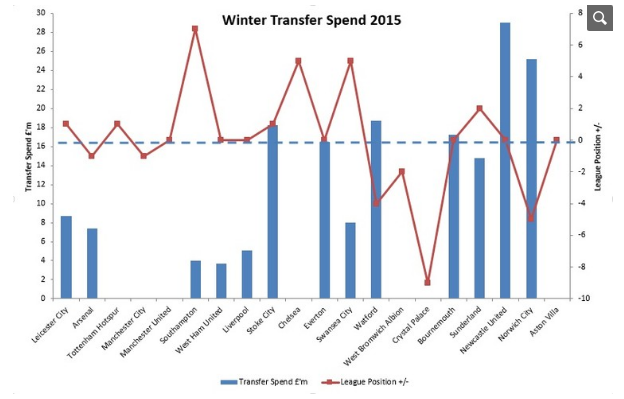

But let’s think about the strategy for a moment here. Should clubs look to invest in youth with a view to a more long-term developmental strategy or throw the kitchen sink at signing experienced players for big money? For many at the bottom end of the league it is the latter strategy that often takes hold despite the returns being so difficult to obtain. The combined spend of clubs in the bottom six last season was £90m – more than half the total – yet only three teams would ultimately survive.

Spending beyond your means does not always guarantee success. It is true that the evidence suggests the most successful clubs with the most money do often outperform their rivals, but the trade-off between financial and sporting performance is hazardous and many clubs now need to chase multiple objectives. Remember the devastating failure at Leeds United in 2003 when creditors were owed nearly £100m after the club chased the dream of playing in the Champions League?

With this comes a need to deviate from the original strategy to maximise short-term performance and retain your position in the world’s richest football league. For example, Swansea City, despite being a little busier this season, is the only club to have generated a net profit on their transfer activity during the last five years, while the two Manchester Clubs have spent over £1 billion between them in the search for the title and European football. This might be good financially, but Swansea also spent Christmas in the relegation zone and sacked manager Bob Bradley after only 85 days in charge. Aston Villa, meanwhile, failed to spend a penny in January last season, effectively sealing their own relegation without putting up a fight.

Newcastle by contrast went big. The club topped the spending table with nearly £30m, but were still relegated, much to the delight of their north-east neighbours, Sunderland, who spent less (still a chunky £18m) and survived.

Watford also went for it, spending about £19m and maintained their league spot but dropped four places. Norwich also spent heavily (£25m) and managed to drop five league places, were relegated and are now playing Championship football in 2016-17.

Watford also went for it, spending about £19m and maintained their league spot but dropped four places. Norwich also spent heavily (£25m) and managed to drop five league places, were relegated and are now playing Championship football in 2016-17.

So, what does this tell us? Well, it tells us that whether your club is struggling, or even challenging for trophies, the temptation is always to spend your way out of trouble. Buying new players appeases the terraces and might even buy the manager some more time. New signings often rekindle the feel good factor but spending money on the wrong players is often worse than doing nothing at all.

( THE AUTHORS ROB WILSON, PRINCIPAL LECTURER IN SPORT FINANCE AND DAN PLUMLEY SENIOR LECTURER IN SPORT BUSINESS MANAGEMENT, SHEFFIELD HALLAM UNIVERSITYTHIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE CONVERSATION.)