![]() Dr Anastasios (Tasos) Theofilou, Principal Academic, Bournemouth University and Evangelos Kontopantelis,Professor in Data Science and Health Services Research, University of Manchester are the authors of this article which was originally published in The Conversation, an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community.

Dr Anastasios (Tasos) Theofilou, Principal Academic, Bournemouth University and Evangelos Kontopantelis,Professor in Data Science and Health Services Research, University of Manchester are the authors of this article which was originally published in The Conversation, an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community.

The English Premier League (EPL) is the most successful football leaguein the world and one of the most successful sports businesses of any kind. But the benefits may be relatively skewed towards people who live in London. Not only has the UK capital had more clubs per fan in the EPL than any other region since the league was created in the 1992/93 season, but their fans have to pay less to travel to see their clubs play away matches.

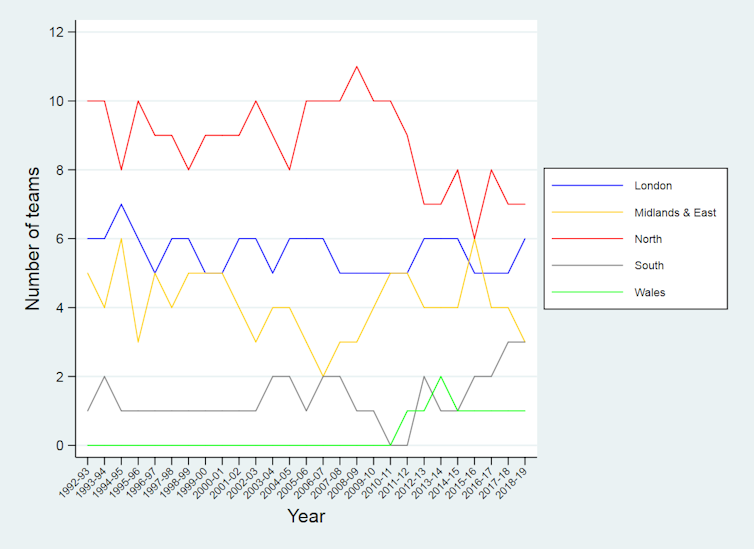

Over the 26 years the league has been in operation, the number of EPL clubs based in London has remained relatively stable at approximately six. Meanwhile, the number of clubs from different regions has fluctuated. The largest reduction was observed in the north of England where the number of EPL clubs fell from ten out of 20 in 1995/96 (when the EPL was reduced from 22 to 20) to seven out of 20 in 2018/19. There was large variation in participation from teams in the Midlands or the east of England and a small increase in the number of clubs from the south and Wales, with the participation of Brighton & Hove Albion FC, AFC Bournemouth and Cardiff City in 2018/19.

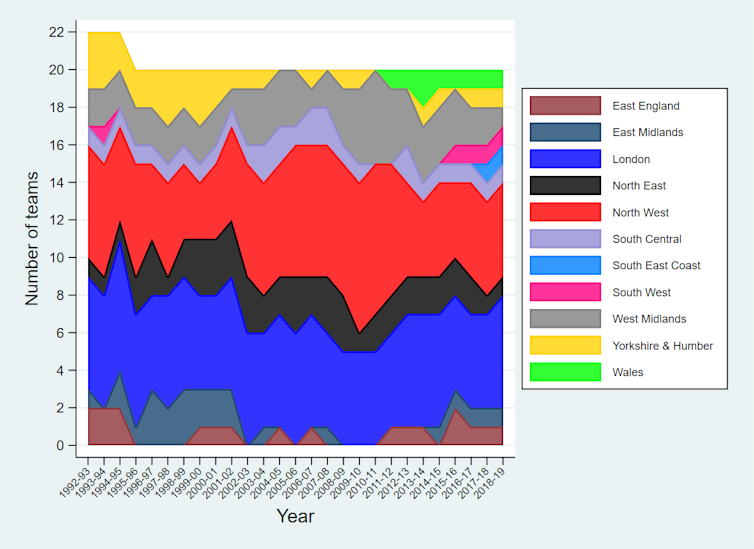

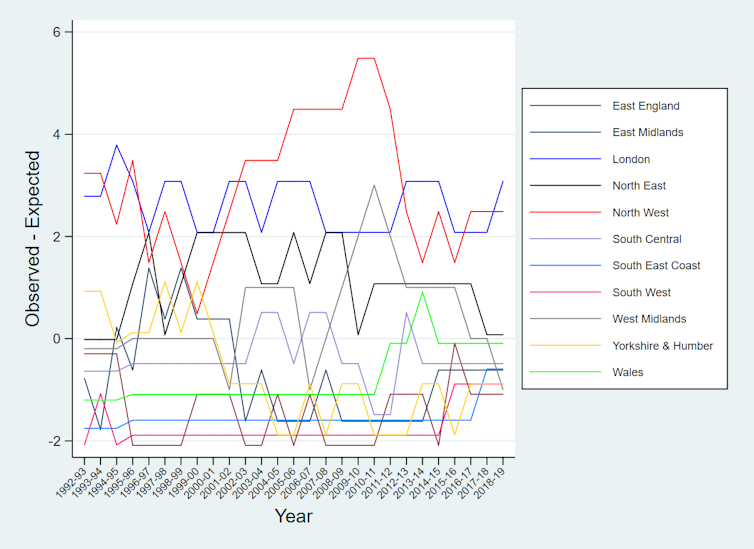

If you dig deeper, you can see that the northwest and, especially, Yorkshire & Humber are the biggest losers over time (Figure 2) – although Leeds United and Sheffield United are currently sitting pretty on the Championship (the second tier of English football) table and may well join the EPL in 2019/20. This implies that there may be stronger regional representation, with Huddersfield (Yorkshire) and Fulham (London) looking destined for relegation to the Championship.

If you adjust this calculation for population size (assuming one club per approximately 2.5m people – distributing fairly 20 clubs across around 51m people), the north of England and London were – and still are – the only two regions punching above their weight. But you can also see a change over time as London has surpassed the north in terms of “over-representation” of clubs from the region. The north’s losses have benefited the south and Wales. Once again, drilling down into lower level regions, it becomes clear that the north-west is the only region comparable to London (Figure 3).

For example, in the 2018/19 EPL season, there were six clubs from London (“observed”) and based on a population around 8,200,000 people from the 2011 Census we would expect around three clubs (“expected”). Meanwhile the north-west of England has a population of around 7.5m so, again, you would expect around three clubs – but there are five in the EPL.

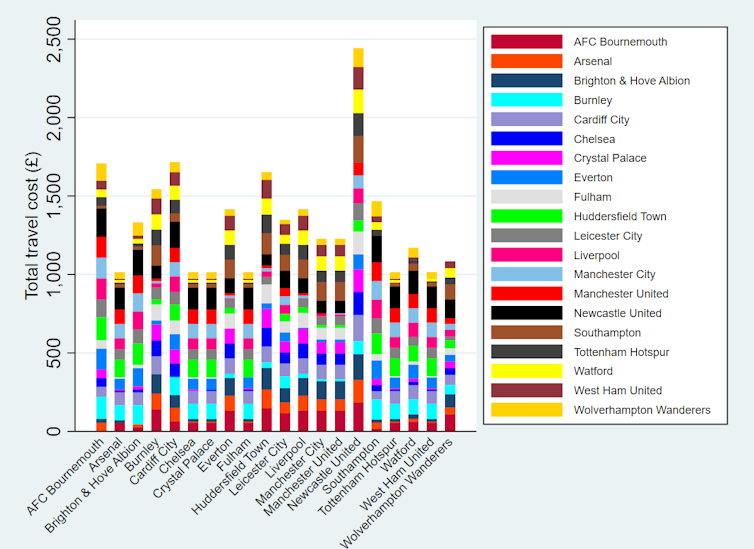

Strain of the train

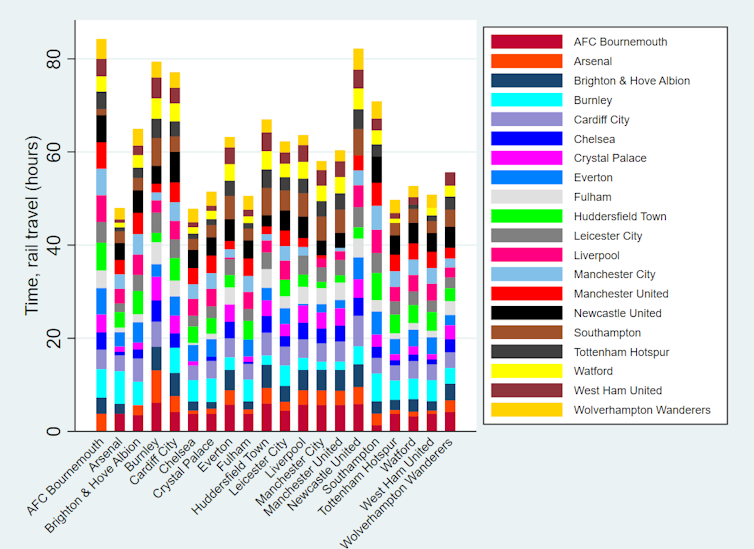

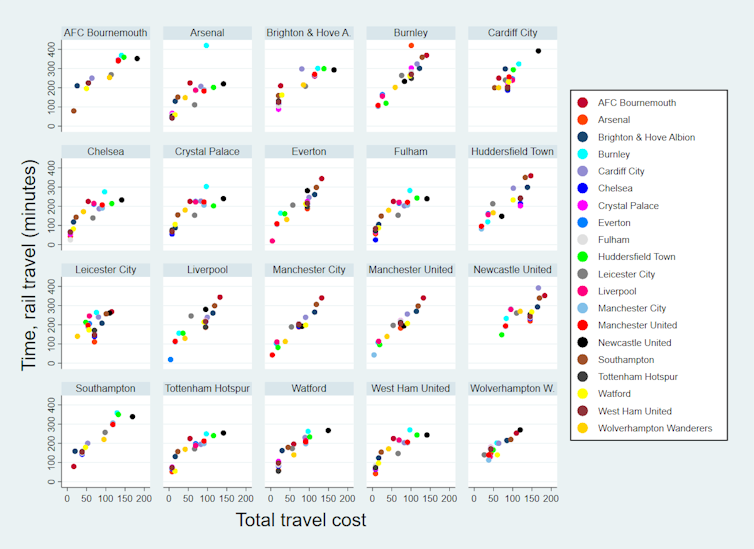

We decided to work out how much things were skewed in favour of London-based clubs and their fans. We calculated how much it costs for fans to follow their clubs on all away EPL fixtures, picking an arbitrary date: Saturday November 3, 2018. We used the most common kick-off time of 3pm and obtained rail and car travel estimates from Google maps and the national rail enquiries website. Unsurprisingly, following Newcastle United, in the northeast, was the most expensive choice – each committed Geordie had to spend around £2,500 on rail fares to attend all of the club’s away matches.

Bournemouth, on the south coast of England, Cardiff City in Wales and Huddersfield Town in Yorkshire were next in line – their fans had to spend more than £1,700. At the other end of the scale, fans of London clubs such as Chelsea, Tottenham and Arsenal faced an average cost of around £1,000. Fans of Liverpool and Manchester clubs had to spend around £1,400 and £1,200, respectively.

In total, rail fares for Newcastle United fans to attend all 19 away matches were in excess of £6.5m (accounting for away fan capacity and assuming sellout crowds). This is a clear outlier, reflecting Newcastle’s remoteness in relation to other clubs – although rail travel time for Novocastrians was better than expected. This at least reflects good services and connections – better than for Bournemouth, Cardiff and Burnley, for example, considering the distances.

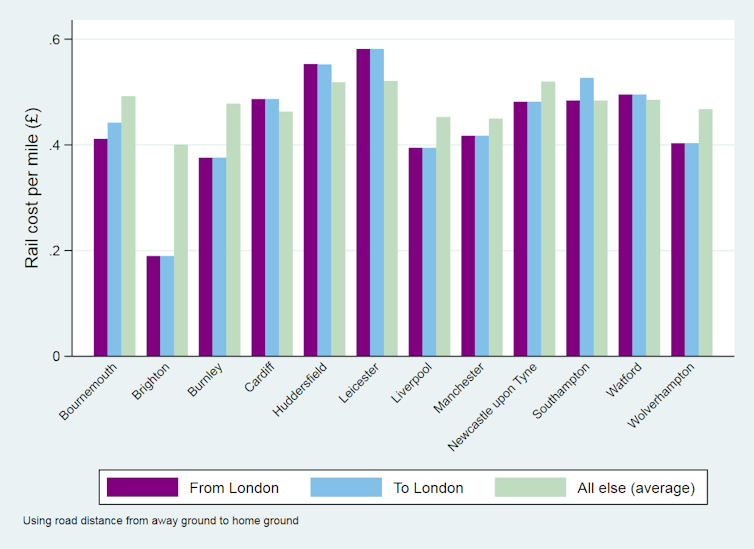

Rail costs per mile further demonstrate a variation – Leicester fans, in particular, have the right to feel particularly aggrieved, with cost per mile travelled to or from London being 0.58p and to or from everywhere else 0.52p (averages for all other cities/towns, excluding London, were 0.43p and 0.47p, respectively).

Interesting point: for Bournemouth and Southampton fans, a return train ticket to London is slightly more expensive than for London-based fans travelling in the opposite direction.

In reality, all these costs are underestimates, since televised matches are played at times that make the lives of travelling fans very difficult – it may be impossible to get a direct train and an overnight stay may be essential, further adding to the costs. And these additional costs are likely to be higher for non-London supporters, since services outside London tend to be less frequent, while overnight stays in London are more expensive.

Level playing field

It becomes evident that football fans have to bear a disproportional cost in time and money, supporting an industry that makes massive profits. So, what can be done? Travelling fans are effectively sports “visitors” and should be treated with reciprocal respect, with more consideration given to televised matches and the distances fans have to travel.

The EPL could also acknowledge the travelling costs for away fans and offer financial support to clubs in a similar way to how broadcast and central income is distributed. This would allow each club to consider a ticket pricing strategy for its own fans or support travelling arrangements. Perhaps clubs could consider selling a bundle product which would include both match and rail ticket. Alternatively (or in addition), the government or football institutions could negotiate fairer “fixed” rail prices.

But it’s not all down to geography, as infrastructure also plays its part. London is at the centre of the biggest sports investments which have made the capital the natural host for national football events. It seems unfair that EFL (or Carabao) Cup finals and FA Cup semi-finals and finals are hosted in London.

Wembley, the “headquarters” of English football, has historically been an integral part of the game in England and is recognised as a global football trademark. But always having cup finals there increases the time and expense for supporters of non-London clubs that are successful in these competitions. Perhaps the region of the finalists should be considered before a venue was decided.

This imbalance is a problem for the EPL as it may have implications for its attractiveness and for generating revenue overall. And, as the so-called “people’s sport”, it’s surely a problem that this emphasis in favour of London and London-based clubs makes life harder for fans with less money to travel to see their clubs play.

Football is one of the most loved sports in the UK and the world, bringing together families and friends over a number of generations. It’s a societal link of togetherness. It shouldn’t give an unfair advantage to London or lead loyal supporters to poverty.