![]() Carl Singleton, Lecturer in Economics, University of Reading and James Reade, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Reading, are the authors of this article which was originally published in The Conversation, an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community.

Carl Singleton, Lecturer in Economics, University of Reading and James Reade, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Reading, are the authors of this article which was originally published in The Conversation, an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community.

Bury Football Club has been expelled from the English Football League after 125 years of membership due to unpaid debts. This is a seismic event in football history. It is the first time a club has been expelled from the third tier of English football and leaves a massive hole in the community where it is based.

Bury’s demise ultimately comes down to economics and bad financial management. The problem with football is that clubs are private enterprises. And yet they are not run like normal companies. Instead of maximising profits, their aim is to maximise success on the pitch.

The peculiar economics of professional sports is that the business aims of clubs do not necessarily align with the desires of their customers, the fans. Despite having an extraordinarily high level of loyalty among fans, Bury was expelled from the English Football League of professional clubs for financial mismanagement.

Loyalty is not only built on longevity but also by clubs becoming focal points within communities, providing leisure activity for friends and family. This ensures that a struggling team like Bury, with its two FA Cup wins in 1900 and 1903, still performed in front of thousands of spectators each week.

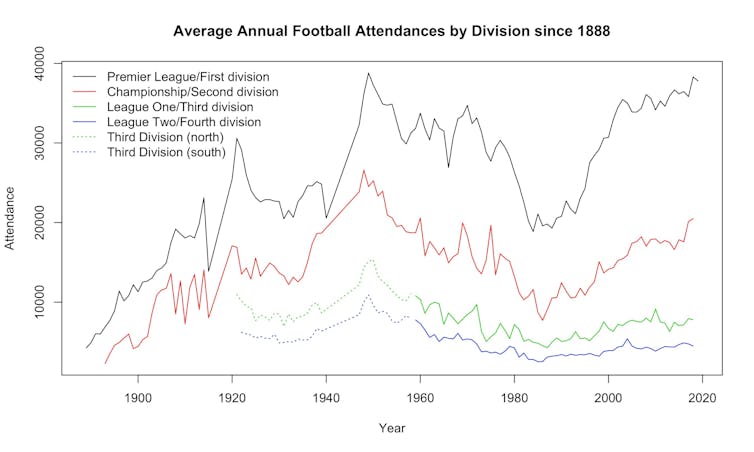

In fact, despite the financial struggles of many clubs, average attendances are as healthy as ever in the lower leagues, as the following graph shows.

The English Football League (EFL) is a collection of chairs of member clubs and has no formal obligation to fans, but its entire existence depends on them. It is precisely fan loyalty that has led to football clubs displaying an unerring ability to survive, and it seems likely this leads to the reckless decisions made by some club owners, which can lead to their decline and even demise.

Bad management

Research by economist Stefan Szymanski suggests issues generally mount up after significant negative shocks such as dropping down a division or falling out of contention for European football. Badly run teams get relegated, sometimes after overreaching, and then fall into insolvency.

The English Football League, in addition to UEFA through its Financial Fair Play regulations, has tried to mitigate against the bad running of clubs. The EFL is supposed to apply a fit-and-proper-person (director’s) test in the case of a club takeover. In its 14-year history, just four people have failed the test. That begs the question: is it fit for purpose?

A more fundamental problem is a lack of financial transparency, which allows clubs to be badly run and mostly hides this fact from the real world, usually until it is too late.

There is more that the English Football League can do to help clubs from falling into insolvency. If negative shocks such as demotion are the main cause of this, then the effects of bad seasons need to be better cushioned. This would reduce rather than enlarge the gaps between divisions.

Sport flourishes when it is interesting, typically meaning there is enough competitive balance. In football, this balance requires economic collusion (which is the opposite of competition) to ensure the differences between teams don’t become too great.

One way the English Football League could achieve this is through distributing the revenues from TV deals more evenly across the leagues. Greater transparency is vital too. The publication of annual, unabbreviated accounts ought to be required. The EFL should remove owners rather than clubs if published accounts are inaccurate or manipulated.

Dishearteningly, the initial musings from the league’s executive chair after Bury’s expulsion suggest it is blissfully ignorant of what the latest research says, with no direct mention of the growing gaps between the divisions, especially the gap between the Premier League and those below it, being a major problem. The EFL is also clearly unwilling to invoke the kind of transparency that would be necessary to prevent any more communities losing their football heritage.