Football in the last century has gone through a massive change. In fact, the modern-day version of the game now requires a player to be at his physical and mental prime even to have a chance to succeed. However, in these changes, there have been essential revolutions that significantly changed the game and have even influenced some parts of the game today. One such important landmark was the development of a system called Catenaccio. As a result, the system developed in Switzerland grew to prominence in the Serie A. Furthermore, the introduction of the system is considered a significant reason why Italy have produced some of the best defenders in football history over the years.

Though no longer in use, the system has some features that several teams have widely used over the last three to four decades. However, Catenaccio is also one of the misunderstood tactical systems in football, with people associating it with some specific stereotypes which have caused it to be unfairly lamented as ‘boring’.

So, what is the Catenaccio and how it revolutionised football?

Read more:

What is Catenaccio?

The word Catenaccio in Italian means’ door bolt, which means a tactical system highly reliant on an organised and watertight defence that seldom gives the opposition a chance to score. One of the major proponents of the system was the Inter Milan side of the 1960s under the legendary manager Helenio Herrera. However, Herrera was not the first user of the system but was definitely the man who took Catenaccio to its best form.

The origins of Catenaccio can be traced back to 1930s Switzerland. During that time, Karl Rappan, the then-national team manager, deployed a 1-3-3-3 formation. This system called the Verrou (French for door bolt), was famous for deploying the Verrouilleur, a player positioned just ahead of the goalkeeper whose job was to clear all the balls and ensure the shot-stopper had to save as few shots as possible.

The Verrouilleur position would later develop into the Libero and also the Sweeper position. Under Rapaan, three centre-backs would play in front of the sweeper, out of which one would be given the role of a playmaker and allowed the freedom to venture forward on the field. At the same time, the two remaining centre-backs’ job was to nullify the opposition’s winger. They could freely do this role, knowing that the Verrouilleur was covering for them even if they got beat.

The system would first gain fame after the Swiis used it to significant effect to eliminate Germany in the first round of the 1938 FIFA World Cup.

Rappan would use the same system during his tenure with Swii side Grasshopper winning them five league titles and seven Swiss Cups between 1936-45.

THREAD : Le verrou suisse de Karl Rappan🇨🇭

Jusque là recordman du nombre de matchs disputés en tant que sélectionneur de la Suisse (77), Karl Rappan va ce soir être rejoint par Vladimir Petković.

Bien avant le Catenaccio, Rappan avait théorisé le verrou suisse.⬇️ pic.twitter.com/QMEJBryGMC

— Q. (@Quentincz_) June 28, 2021

The Italian Catenaccio

However, Rappan’s system would find more success south of the Alps in Italy. The 1950s was a turbulent time in Italian football. The Superga air disaster had claimed the lives of the entire Torino team in 1949. The team had won four back-to-back Serie A titles, and their demise followed a phase where the league was dominated by Juventus, AC Milan and Inter Milan, with the other teams reduced to the status of ‘also rans’.

So, the other teams were desperately searching for a system that would help them bridge the gap to the top three. Under these circumstances, Padova’s manager Nereo Rocco turned to the Catenaccio. Rocco had used such a system during his spell as Triestina’s manager, helping them finish second in Serie A.

He would repeat the same trick with Padova taking them to a third-place finish. It was during this phase that the top team in Italy would start taking the Catenaccio seriously. And in 1961, AC Milan put their faith in Rocco.

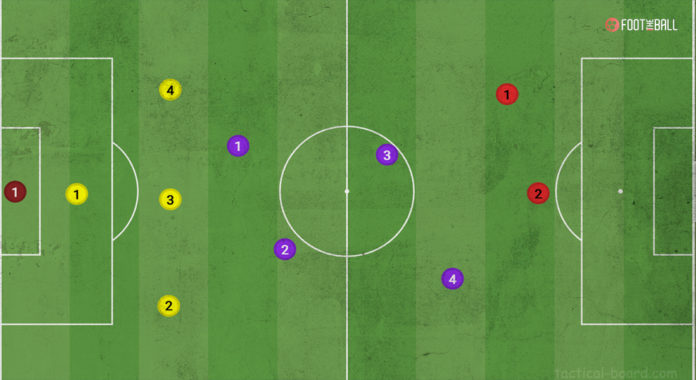

Rocco used two formations, 1-4-4-1 and 1-4-3-2, during his time at AC Milan. In the formation, the lone sweeper played behind a four-man backline in which one defender was allowed to act as a playmaker and venture forward, which meant that the other three centre-backs were tasked with stopping the wingers.

This system brought AC Milan to win ten trophies, including two Serie A, three Coppa Italia and two European Cups.

Read more:

Inter Milan’s Catenaccio

While AC Milan were winning the Serie A title, their city rivals, Inter Milan, under Helenio Herrera, were playing a far more attacking system. However, this didn’t help them win the title, and with his job on the line, Herrera turned towards the Catenaccio.

However, he introduced several modifications to it, making it the best version of Catenaccio in the game’s history. The manager deployed skipper Armando Picchi as the sweeper behind a four-man defence. The two full-backs were given the licence to go forward, especially left-back Giacinto Facchetti.

One of the major advantages that Inter Milan had was that Picchi was probably the greatest sweeper when it came to playing accurate long balls. He often used this passing range to find Facchetti and right-back Tarcisio Burgnich, who would use the wings to start fast counterattacks.

The catenaccio formation of Inter with Helenio Herrera 1963-1964-1965. pic.twitter.com/Y0Ica8SzhR

— Mohamed Rtimi (@moertimi) May 8, 2019

The change worked like a charm as Inter Milan won three Serie A titles, two European and two Intercontinental Cups. Using the Catenaccio didn’t have any effect on Inter’s attacking capabilities, as they finished as the top scorers in two of their title-winning seasons.

However, their defeat to Celtic in the 1967 European Cup Final saw the start of the decline of Catenaccio. In the match, the Scottish champions used a ferocious attacking tactic that jolted the Inter backline, forcing them into committing mistakes on which the Celts pounced.

Modern use of Catenaccio

While the Catenaccio is not used in football anymore, its imprint can still be found in many teams. However, the teams that did copy them copied only the defensive attributes, which have caused the system to be associated with parking-the-bus tactics that involve no attacking flair.

One of the prime examples of it was Greece’s Euro 2004 campaign under manager Otto Rehhagel. With a squad with limited talent, Rehhagel opted for an ultra-defensive strategy forming a string backline of Giourkas Seitaridis, Michalis Kapsis, Traianos Dellas, and Takis Fyssas with the defensive-minded Kostas Katsouranis acting as the number six ahead of them.

The tactics worked perfectly as Greece won the trophy by scoring only seven goals in their six games. Another example is the 2009-10 Inter Milan side led by Jose Mourinho, who used these tactics, especially against the sextuple-winning Barcelona in the semi-finals of the 2010 UEFA Champions League.

Helenio Herrera said that Catenaccio was associated with ultra-defensiveness because the managers who copied his tactics did it incorrectly, not taking in all the attacking principles of the system. He pointed to his left-back Fachetti, who hit double figures in a Serie A season, as one of the reasons why his system was a perfect balance between attack and defence.

However, the system did change Italian football and helped produce world-class defenders such as Franco Baresi, Paolo Maldini, Alessandro Nesta, and Fabio Cannavaro. In addition, it also came to Italy’s rescue in the 1982 FIFA World Cup, where they used some of its principles to win the World Cup against far superior teams.